Operating Assumptions December 2014

Ronald S. Waife

Honesty is the Only Policy

When was the last time you told someone the whole truth? When was the last time you thought someone was telling you the whole truth? Have you told that under-performing monitor that he is, in fact, under-performing? Did you tell your sponsor about the problems you started having with that investigative site? Did you tell your customer about the true delivery date for the next software release? Did you tell your employees how much bonus you are making from their long hours or work? These are all examples of how, every day, we treat each other dishonestly. You can argue that these “white lies” make work easier, but I would argue they strongly contribute to the highly inefficient state of clinical research. Honesty isn’t the best policy, it’s the only policy.

Widespread and Too Easy

Let me emphasize from the start that when I discuss “dishonesty” in this column I am not talking about criminal behavior – dishonest handling of trial data, noncompliance with regulations, cutting corners in analytical rigor, insider trading, and so on. I’ve never seen them and they are not my point. I’m talking about “process dishonesty” – dishonesty in the way we treat each other every day.

There are so many examples of dishonesty in everyday research life that any reader can quickly provide their own list. Here are just a few:

- Sponsors lie to CROs about when the trial is going to start.

- CROs lie to sponsors about the qualifications of who is going to work on their trial.

- Clinicians lie when they say “this is the final protocol.”

- Quality Assurance is often lying when they say “the FDA requires this.”

- Every department lies to each other when they set a deadline, knowing the deadline will be missed and leaving themselves room to maneuver.

- Sponsors lie to their own staff about plans for job elimination or outsourcing.

- Consultants lie when they tell clients what they want to hear, instead of what they found.

- Sponsors lie when they tell consultants they want help with “x”, when they actually want justification for “y”.

- Upper management lies when they tell their direct reports how much money is in the budget for next year, and their direct reports lie about how much money they need.

So okay, this is hardly unique to clinical research and is universal and as old as time. It has survived as standard business practice for so long because it doesn’t seem to matter. But I suggest it does matter, a lot, not just on ethical grounds, but to sponsors who are trying to change their approach to research and make the development of new therapies faster and less costly.

Inefficient Dishonesty

How does all this hurt clinical development, if it is such a standard business practice? Dishonesty and efficiency don’t mix:

- If you put somebody on a team because you have to, instead of because they are qualified, that leads to inefficiency.

- If you can’t tell someone they are not good enough at their job, your employing inefficiency.

- If you avoid the opportunity to provide constructive criticism, that’s permitting inefficiency.

- If requestor and bidder play a game of “chicken” when negotiating a budget, resulting in weeks of delay in the name of “best practice contracting” or Sarbanes-Oxley, the only best practice we are achieving is expert time-wasting.

- We all know the truism that it takes three times, or ten times more resources to fix a problem downstream rather than when it happens. But because being honest upfront is not safe, we’d rather “kick the can down the road”, wasting more time.

- You will not have a chance to really know if your in-house staff has the ideas, skills and flexibility to perform better, if you don’t tell them that their performance issues so dire that you’ve already decided to outsource their jobs.

I think that white lies are so ingrained, they are second nature. We congratulate ourselves for avoiding confrontation, which usually means we avoided the truth. The financial, personal and professional pressures to bypass hard truths are all too real and way too strong. Our slippery sidesteps are all too understandable. And yet if we start to believe our own white lies, no one can save us from ourselves.

Mistrust and Passivity as Symptoms

Our problem with honesty in our research process creates deeper and more subtle negative effects. Mistrust and passivity can be the direct byproducts of a failure of honesty. Indeed they contribute to dishonesty in a nasty feedback loop. We mistrust our CROs and they mistrust their customers because disinformation has become the mode of communication. Our staff mistrust our managers when outsourcing or acquisitions are announced out of the blue. And nobody believes the software vendor’s delivery date, or the first specifications of a protocol, because it is not acceptable for us to acknowledge unpredictability or unreasonable deadlines.

Passivity is a cousin of mistrust and dishonesty. If I don’t trust you, and I’ve learned to speak in white lies, my best course of action is to lay low, do only as I’m told, and otherwise stay passive. No wonder research executives today decry the rampant lack of urgency and energy in their organizations!

Getting to Honest

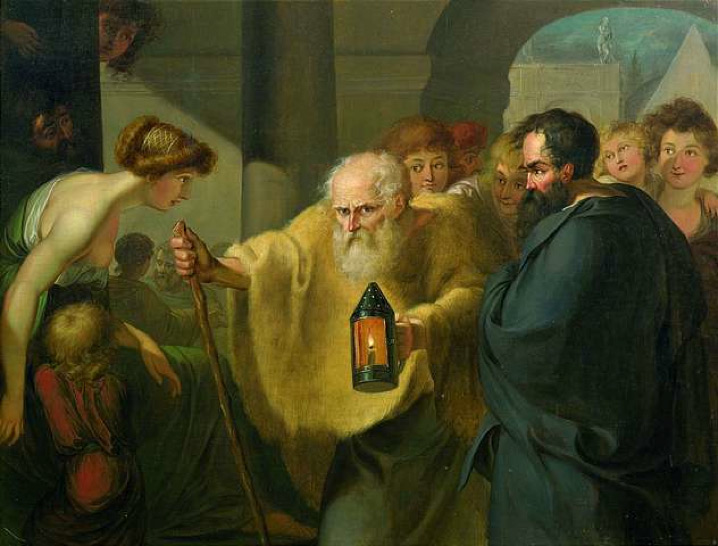

Diogenes is described as searching high and low in ancient Athens, in vain, for an honest man. Diogenes was also a philosopher of Cynicism, whose modern meaning may be too harsh and excessively pessimistic for this topic. Not only can we find honest people, we can make them.

How do we get more honest in our treatment of each other?

- Make it safe to be honest: I think few of us think we can be honest with our bosses, staff, providers or customers without negative consequences. We need to make honesty permissible and desirable.

- Make it a cultural imperative: we should not only make it safe to be honest, we need to recognize it as a necessity for our organizations’ efficiency, productivity, and respect.

- Educate each other about our jobs or “walk a mile in their shoes”. The more we understand the work, the motivations, the potential and the limitations of the work of others, the more we will understand and accept honestly delivered information, and the more honest we can be in our own communication.

- Demonstrate and model honesty in our own behaviors. We’ve described how this can be risky – who’s going to go first? I don’t think we can wait for the other guy to blink. Instead, we need the courage to trust and respect others enough to treat them with honesty and bear the consequences. In time, we can start a safe and productive feedback loop.

I think I hear the Golden Rule echoing nearby.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.